Venerdì 7 dicembre

ore 8.00 Registrazione dei Partecipanti presso la Segreteria (Hotel Africa, Avenue Bourguiba, 5° piano, anticamere delle due sale Zambèze). Posters, esposizione di libri.

ore 9.00 Apertura del Convegno (Salle Zambèze 1, 5° piano)

Saluto di Paola Ruggeri, Centro di Studi Interdisciplinari sulle Province Romane dell’Università di Sassari.

Saluto di Kamel Bchini, Agence de Mise en Valeur du Patrimoine et de Promotion Culturelle.

Saluto di Faouzi Mahfoudh, Institut National du Patrimoine.

Saluto di Mohamed Zinelabidine, Ministre des Affaires Culturelles.

Saluto di Lorenzo Fanara, Ambasciatore d’Italia a Tunisi.

Saluto di Attilio Mastino, Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Cartagine.

Saluto di Antonello Cabras e Angela Mameli, Fondazione di Sardegna.

Saluto delle Autorità

Consegna del premio Amedeo Maiuri. Interventi di Umberto Pappalardo, Piero Bartoloni e Lorenzo Fanara.

«L’epigrafia del Nord Africa: novità, riletture, nuove sintesi»: relazione introduttiva di Samir Aounallah (Tunis).

Ricordo di Enrique Gozalbes Cravioto (intervento di Cinzia Vismara).

Presentazione dei volumi:

- Carthage, maîtresse de la Méditerranée, capitale de l’Afrique (Histoire & Monuments, 1), (IXe siècle avant J.-C. – XIIIe siècle). AMVPPC, SAIC Sassari, Tunisi 2018, a cura di Samir Aounallah e Attilio Mastino (intervento di Maria Antonietta Rizzo).

- J.-P. Laporte, M. Guérout, Le Magenta, du naufrage à la redécouverte (1875-1995), CNRS Éditions, Paris 2018 (intervento di Piero Bartoloni).

- Bruno D’Andrea, “Bambini nel limbo”. Dati e proposte interpretative sui tofet fenici e punici (Collection de l’École Française de Rome, 552), Roma 2018 (intervento di Sergio Ribichini).

- Nabil Kallala, Joan Sanmartí (dir.),Althiburos I. La fouille dans l’aire du capitole et dans la nécropole méridionale, Tarragona: Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica, 2011 (Col.lecció Documenta, 18) e Nabil Kallala, Joan Sanmartí (dir.); Maria Carme Belarte (ed.), Althiburos II. L’aire du capitole et la nécropole méridionale: études, Tarragona: Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica, 2016 (Col.lecció Documenta, 28) (intervento di Sergio Ribichini).

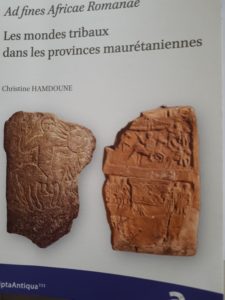

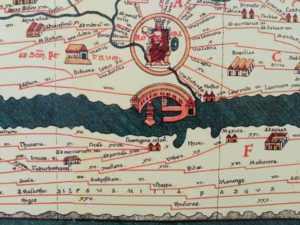

- Christine Hamdoune, Ad fines Africae Romanae. Les mondes tribaux dans les provinces maurétaniennes (intervento di Attilio Mastino).

- L’eau dans les villes du Maghreb et leur territoire à l’époque romaine, Bordeaux, Ausonius, Coll. Mémoire n° 54, 2018, a cura di Veronique Brouquier-Reddé e Frédéric Hurlet (intervento di Cinzia Vismara).

- Paul-Albert Février, Michèle Blanchard-Lemée, avec la collaboration de François Baratte, Hany Kahwagi-Janho, Patrizio Pensabene, L’édifice appelé «Maison de Bacchus», à Djemila (intervento di Amina Aïcha Malek).

- Vie et genres de vie dans le Maghreb antique et médiéval, a cura di Abdellatif Mrabet (intervento di Pier Giorgio Spanu).

- Cupae. riletture e novità. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi (Oristano 5-7 settembre 2016), a cura di Giulia Baratta (intervento di Mounir Fantar).

- Libya Antiqua, VI-X (2011-2017) (intervento di Mohamed al-Faloos).

ore 11.30 Sessione I: “Le città”

Khaled Marmouri, Ginette Di Vita-Evrard (Paris): L’apport des inscriptions de l’amphithéâtre et de la schola à la prosopographie lepcitaine.

Louis Maurin (Bordeaux): Un nouveau sufes Maior de Thugga.

Samir Aounallah (Tunis): Les statuts juridiques des communautés de l’Afrique romaine (-146/-46).

Samir Aounallah (Tunis), Attilio Mastino (Sassari), Alessandro Teatini, Antonio Ibba, Maria Bastiana Cocco (Sassari), Antonio Corda, Piergiorgio Floris (Cagliari), Alberto Gavini (Sassari), Lamia Abid, Ali Cherif (Tunis): Le nuove scoperte epigrafiche a Thignica, Aïn Tounga.

Paola Ruggeri, Salvatore Ganga (Sassari): Il tempio di Nettuno a Thignica e la colonizzazione di Thugga e Thubusicum Bure sotto Gallieno.

David Serrano Ordozgoiti (Madrid): Autorappresentazione imperiale della domus Licinia Augusta nell’epigrafia latina del Nordafrica (253-268 d.C.): una nuova sintesi.

Inaugurazione della mostra dei posters

ore 13.30 Pranzo libero

ore 15.30 Ripresa dei lavori (Salle Zambèze 1)

Sessione I: “Le città”

Christopher Dawson (Greater Sudbury): Populus de suo posuit. The People’s Response to Remittances at Gigthis.

Alessandro Abrignani (Roma): Colonia Septimia Vaga. Fonti epigrafiche e topografia urbana.

Salem Mokni (Sfax): Données sur une étape de la romanisation juridique de la colonie romaine de Thaenae (actuelle Thyna, Tunisie).

Roger Hanoune, Christine Hoet-Vancauwenberghe (Lille): Une nouvelle inscription de Pupput: la rénovation d’un édifice public et la province Flavia Valeria Byzacena.

Mondher Brahmi (Tunis): Documents épigraphiques inédits de la cité latine de Capsa/Gafsa.

Cheddad A. Mohcin (Martil): Tanger à travers ses inscriptions latines.

ore 17.00 Sessione II: “Epigrafia storica e giuridica”

Arbia Hilali (Sfax): Les affranchis et le culte de la gens Augusta: le témoignage de P. Perelius Hedulus à Carthage.

Hernán González Bordas (Alcalá de Henares), Ali Chérif (Tunis): Henchir Hnich (région du Krib, Tunisie), la découverte de la lex Hadriana de agris rudibus et trois autres inscriptions.

Lotfi Naddari (Tunis): Nouvelles considérations sur l’œuvre municipale d’Antonin le Pieux en Afrique et en Italie.

Mourad Chetoui, Cristophe Hugoniot (Tours): Les proconsuls d’Afrique sous Marc Aurèle.

Marc Mayer (Barcelona): Vibia Aurelia Sabina y su presencia epigráfica en África.

Hamden Ben Romdhane (Tunis): Nouvelles précisions sur la famille du clarissime africain C. Memmius Fidus Iulius Albius.

Antonio Ibba (Sassari): Equites africani: un aggiornamento (1972-2017).

Carolina Cortés-Bárcena (Santander): La perpetuación de la memoria del patronato cívico en Africa proconsularis.

Samir Aounallah (Tunis), Frédéric Hurlet (Paris Nanterre): Deux nouvelles inscriptions de Pheradi Maius (Sidi Khlifa).

Abdellatif Rhorfi (Fès): L’aristocratie autochtone de Volubilis d’après les inscriptions latines.

Dibattito conclusivo

ore 21.00 Cena (libera)

Sabato 8 dicembre

ore 9.00 Inizio dei lavori (Salle Zambèze 1 e Salle Zambèze 2, 5° piano)

Salle Zambèze 1

ore 9.00 Sessione II: “Epigrafia storica e giuridica”

Ari Saastamoinen (Helsinki): New Building Inscriptions from Roman North Africa.

Mohamed El-Mostafa Filah (Alger), Souad Slimani (Constantine): Un nouveau dossier épigraphique dans le Hodna Occidental.

Mounir Fantar (Tunis), Raimondo Zucca (Sassari): La viabilità del promunturium Mercurii: i miliari.

Estefania Benito (Madrid): La visión romana de los pueblos líbicos a partir de las fuentes epigráficas latinas.

ore 10.00 Sessione III: “Epigrafia militare”

Anthony Álvarez Melero (Sevilla): Préfets des ouvriers issus des provinces africaines.

Sabine Lefebvre (Dijon): La legio III Augusta dans la lutte pour le pouvoir impérial en 238. Un exemple de pratique de l’abolitio memoriae.

Mela Albana (Catania): Coniuges, uxores e sponsae di militari nelle epigrafi lambesitane.

Mohamed Grira (La Manouba): L’épitaphe de la famille d’un vétéran de la legio X Gemina Pia Fidelis provenant de Sufes (Sbiba, Tunisie centrale).

ore 11.00 Sessione V: “Iscrizioni funerarie”

Stefan Ardeleanu (Heidelberg): L’épigraphie funéraire de l’Afrique du Nord tardo-antique: bilan, problèmes et perspectives de la recherche récente (1988-2018).

Claude Briand-Ponsart (Caen): Fondations funéraires, fondations évergétiques: bilan et propositions pour une typologie.

Jesper Carlsen (University of Southern Denmark): The Necropoleis of the familia Caesaris in Carthage reconsidered.

Mohammed Abid (Tunis): Les vernae en Afrique romaine. Étude épigraphique et historique.

Monique Dondin-Payre (Paris): Trois inscriptions funéraires inédites d’Uchi Maius.

Intissar Sfaxi (Aix-en-Provence): Helula Iulia Sutta, l’étrange nomenclature citoyenne de Bulla Regia.

Moheddine Chaouali (Tunis): Réflexions autour du milieu des notables à Simitthus (Tunisie) à travers une épitaphe inédite de Iulia Suavis et Veturius Felix.

Djahida Mehentel (Alger): À propos d’une nouvelles inscription de la région de Constantine.

Mustapha Dorbane (Alger): Nouveaux témoignages sur les Gargilii de Djemila et de leur mausolée.

Seddiki Azeddine, Said Khacha (Alger): Les affranchis des Gargiliae Praetorianae de Cuicul (Djemila, Algérie).

Khadidja Mansouri (Oran): L’éloge dans l’épigraphie funéraire de Mauretanie Cesarienne sous l’empire romain.

Dibattito conclusivo

ore 9.00 Salle Zambèze 2

Sessione IV: “Vita religiosa”

M’hamed Hassine Fantar (Tunis): Du libyco-punique au latin dans un sanctuaire de Téboursouk.

Rossana De Simone (Enna), Francesco Tomasello (Catania): Su una bilingue latina e punica da Thuburbo Maius (ILT 732): l’apax ‘cella proma’ tra epigrafia, linguistica e dati archeologici.

Giovanni Di Stefano: Dei e dee da Cartagine a Roma sulla via del trionfo dopo il 146 a.C. Alcune riletture incrociate.

Valentino Gasparini (Madrid): Chiamami col tuo nome. Una nuova proposta di analisi dell’impiego dei gentilizi come epiteti divini nell’epigrafia dell’Africa romana.

Meriem Sebaï (Paris): Une nouvelle inscription votive consacrée à Saturnus Neapolitanus.

Juan Lewis (Edinburgh): Agnus vicarius. A Substitute for Child Sacrifice?

Mustapha Khanoussi, Faycel Stiti (Tunis), Paola Ruggeri (Sassari): Le culte du dieu Mars et la délimitation du territoire de la colonie romaine de Simitthus, en Numidie proconsulaire, à la lumière de nouvelles découvertes.

Abid Hosni (Tunis): Castor et Pollux dans une nouvelle dédicace d’époque sévérienne dans le Municipium Septimium [—] (Hr Debbik), en Proconsulaire (Tunisie).

Jalel Mabrouk (Tunis): Le terme cultor dans l’épigraphie latine d’Afrique.

Nora Bouhadoun (Alger): Une sacerdos de Cereres à Madaure.

Salim Annane (Alger): Deus Sanctus Dracho: inscription inédite de Timezouine (Saida).

Abdelaziz Bel Faida (Kénitra): Les cultes à mystères en Afrique du Nord antique. Le cas de Mithra: témoignages épigraphiques et archéologiques.

Néjat Brahmi (Paris): Textes et images du Genius en Maurétanie Tingitane.

Layla Es-Sadra (Rabat), La Domus Augusta de Volubilis.

Dibattito conclusivo

ore 13.30 Pranzo libero

ore 15.30 Ripresa dei lavori (Salle Zambèze 1)

Sessione VI: “Altre epigrafie. Rapporti con altre province”

Ouiza Ait Amara (Alger): L’épigraphie libyque et son apport à la connaissance de la Numidie.

Mohamed El Mhassani (Alicante): La situación lingüística y el proceso de la romanización en Marruecos: una realidad histórica vista a través de las inscripciones latinas.

Hamid Arraichi (Oujda): Histoire du Maroc antique et approches épigraphiques.

Jeremy Rossiter (Edmonton): Some Roman Brickstamps from Carthage not included in CIL VIII.

Abdellatif Mrabet, Mohamed Riadh Hamrouni, Tarek Mani (Sousse): Encore des marques amphoriques découvertes à Sullecthum (Salakta, Tunisie): vers une évaluation globale d’un catalogue en constante croissance.

Celia Sánchez Natalías (Zaragoza): …cadat, frangat, vertat:

relectura de la defixio hadrumetina DT 282.

Anis Hajlaoui (Tunis): Témoignage épigraphique sur un atelier de mosaïque en Byzacène intérieure.

Nedjma Serradj-Remili (Alger): Une nouvelle lecture de quelques inscriptions latines d’Algérie à la lumière d’œuvres musivales.

Jean-Pierre Laporte (Paris): Découvertes récentes en Kabylie.

ore 17.45 Sessione VII: “Mondo tardo-antico”

Mohamed-Arbi Nsiri (Paris-Nanterre): Les constructions des évêques africains d’après les inscriptions tardo-antiques.

Christine Hamdoune (Montpellier): Relecture d’inscriptions chrétiennes des Maurétanies.

François Baratte (Paris Sorbonne), Fathi Béjaoui (Tunis): Moines et moniales dans l’épigraphie africaine: bilan et nouveaux documents.

ore 18.30 Sessione VIII: “Musei. Storia degli studi”

Nacéra Benseddik (Alger): Un lapidaire épigraphique à l’École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts d’Alger.

Luisa Musso, Laura Buccino, Ginette Di Vita Evrard, Caterina Mascolo (Roma): “Quaderni di Archeologia della Libya”: il nuovo progetto editoriale.

Antonio Maria Corda, Sandra Astrella (Cagliari), Cartagine studi e ricerche (CaSteR): la rivista della Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Cartagine.

Dibattito conclusivo

ore 19.30 Intervento conclusivo di Attilio Mastino.

ore 21.00 Cena (libera)

Domenica 9 dicembre

ore 8.00 Escursione a Thugga (Samir Aounallah, Nesrine Nasr)

ore 16.00 Partenze